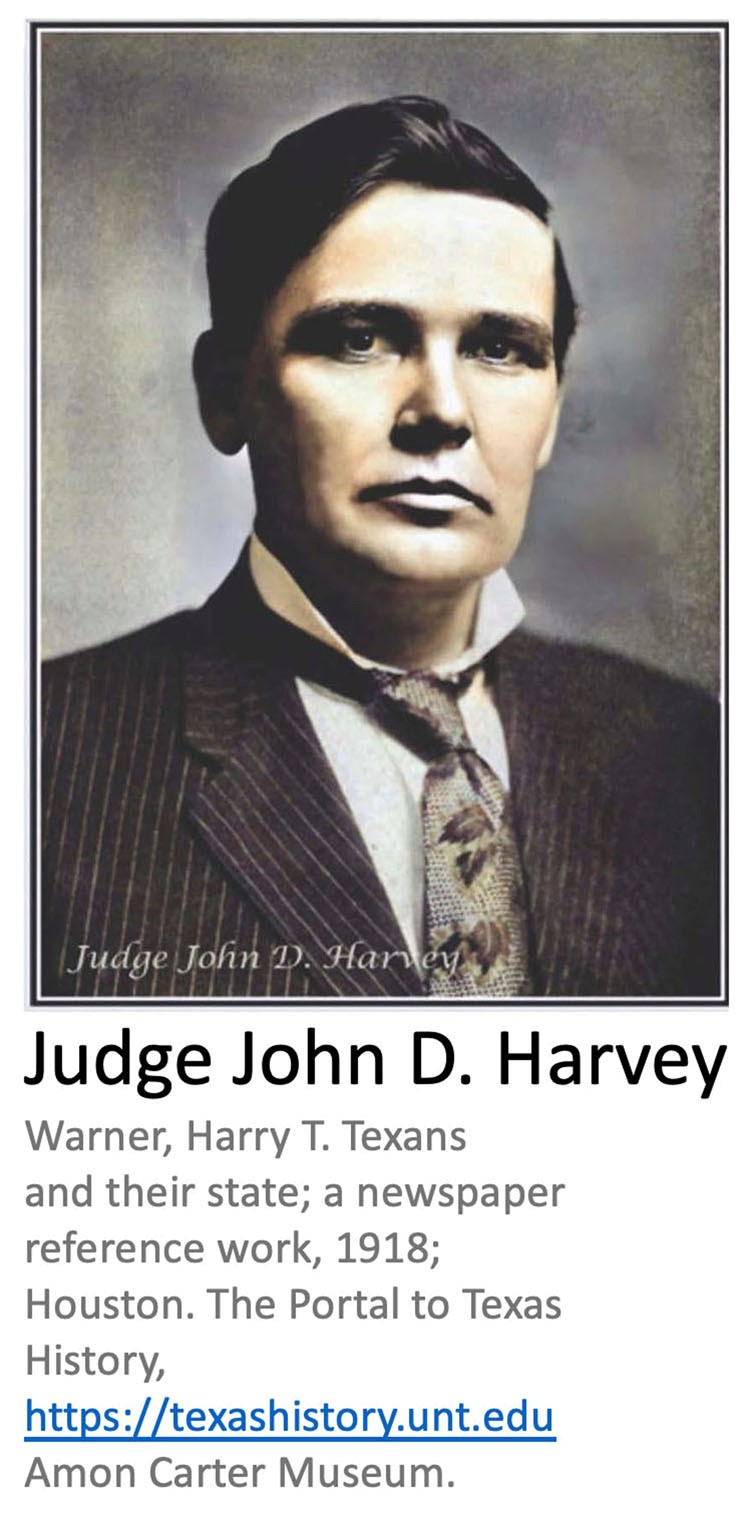

John Dixon Harvey (1873-1949)

John Dixon Harvey’s family was well-known in Hempstead, Waller County (formerly part of Austin county), where his dad, Anson Jones Harvey, was a land lawyer and former Confederate veteran. Young John Dixon earned money as a farm laborer to pay for his studies at the University of Texas. Later as a young lawyer in Hempstead, he approached his law practice as seriously as his university courses. Other Waller County attorneys recounted seeing John’s shadow outlined on the office window of the Farmer’s National Bank where John would spend nights researching and studying the law for upcoming cases. In 1915, Judge Harvey was the first appointed judge of the newly created Texas 80th District Court of Harris and Waller counties. The Houston Bar Association members regarded Judge Harvey as “possessing one of the finest analytical minds on any bench”.1

John Dixon Harvey’s family was well-known in Hempstead, Waller County (formerly part of Austin county), where his dad, Anson Jones Harvey, was a land lawyer and former Confederate veteran. Young John Dixon earned money as a farm laborer to pay for his studies at the University of Texas. Later as a young lawyer in Hempstead, he approached his law practice as seriously as his university courses. Other Waller County attorneys recounted seeing John’s shadow outlined on the office window of the Farmer’s National Bank where John would spend nights researching and studying the law for upcoming cases. In 1915, Judge Harvey was the first appointed judge of the newly created Texas 80th District Court of Harris and Waller counties. The Houston Bar Association members regarded Judge Harvey as “possessing one of the finest analytical minds on any bench”.1  [^Judge Harvey Image] In December 1920, a month after Judge Harvey’s historic Case 91196 ruling for Harris County woman’s suffrage, he sponsored a bill in the Texas Legislature requiring men to pay child support if they were not financially supporting their children after divorce. This bill became known as “Harvey’s Child Support Bill.”2 The bill received the endorsement of almost every women’s club in Houston, yet it was killed in the Texas House in early 1921.3 Another effort in 1924 died in the Texas Senate as well.4

[^Judge Harvey Image] In December 1920, a month after Judge Harvey’s historic Case 91196 ruling for Harris County woman’s suffrage, he sponsored a bill in the Texas Legislature requiring men to pay child support if they were not financially supporting their children after divorce. This bill became known as “Harvey’s Child Support Bill.”2 The bill received the endorsement of almost every women’s club in Houston, yet it was killed in the Texas House in early 1921.3 Another effort in 1924 died in the Texas Senate as well.4

In 1924, Judge Harvey ran for re-election on an anti-Klan platform and lost. Soon afterwards, Texas Governor Miriam A. Ferguson named him to the Supreme Court Commission of Appeals for a six-year term. The commission’s purpose was to hear cases in the Texas Supreme Court backlog. The Commissioners’ decisions would be approved by the Texas Supreme Court or the Court of Criminal Appeals in order to constitute precedent.5 Judge Harvey served for nineteen years until he resigned because of ill health. He died in 1949 and is buried in Austin. He and his wife, Henrietta, were childless and lavished attention on their niece and nephews. The Harvey’s donated funds to support Houston’s orphans.6

"Judge Harvey Image Warner, Harry T. Texans and their state; a newspaper reference work, book, 1918; Houston. (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth41332/: accessed August 22, 2020), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Amon Carter Museum.

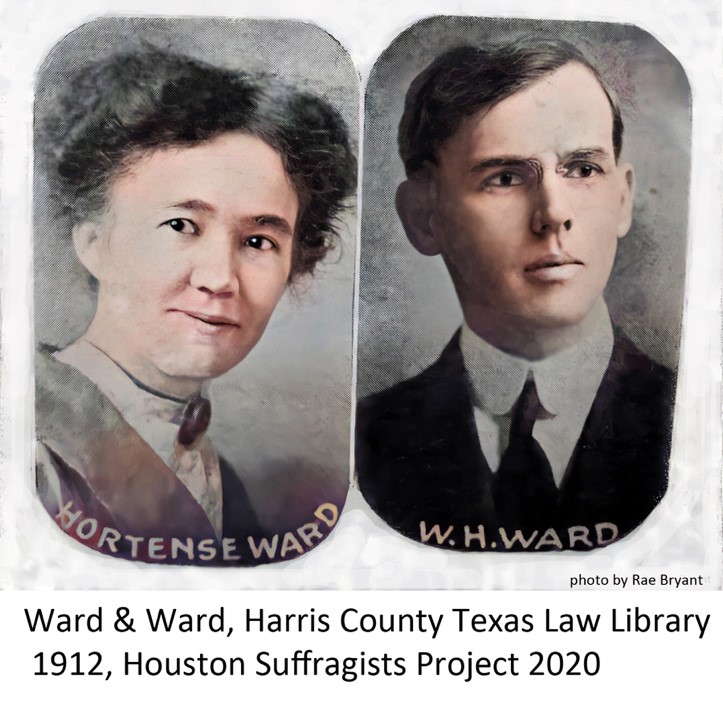

Judge William Henry Ward (1879-1939)

Hortense Sparks Ward and William Henry (W.H.) Ward were a Houston power couple as well as legal partners. W.H. Ward was elected for a four-year term as Harris County Judge in a whirlwind campaign in 1912 when he was 33 years old. He was the youngest Harris County Judge while concurrently continuing as a municipal probation judge. Judge Ward’s positions gave the Wards political and social influence in Houston which was the largest city in Texas.

Hortense Sparks Ward and William Henry (W.H.) Ward were a Houston power couple as well as legal partners. W.H. Ward was elected for a four-year term as Harris County Judge in a whirlwind campaign in 1912 when he was 33 years old. He was the youngest Harris County Judge while concurrently continuing as a municipal probation judge. Judge Ward’s positions gave the Wards political and social influence in Houston which was the largest city in Texas.

According to W.H. Ward’s 1939 Houston Chronicle obituary, he was mainly remembered for improving and developing the Harris County road system with a $1,000,000 bond issue. However, a closer look at Ward’s 1912-1916 term reveals he was responsive to women’s concerns. For example, Tuberculosis (T.B.) was a growing problem in Texas with over 5,000 deaths annually. Harris County sent mild T.B. cases to out-state residency locations whereas for severe cases, the city and county paid individuals and families to attend the sick in their homes or in boarding houses. In 1913, the Anti-Tuberculosis League received Judge Harvey’s support to establish a free treatment dispensary and free supplies on county property near the jail. By 1915, a more permanent hospital structure was constructed providing better and more standardized care.

Judge Ward was instrumental in the purchase of the South Houston School for Boys building that housed almost 100 boys assigned through his probation court. As a unique program in the South, boys received vocational as well as academic schooling. Some boys sold newspapers and others were active as Boy Scouts. In contrast to punitive institutions common at the time, this environment encouraged good habits, skills, and socialization, giving youth a chance to be successful adults. Judge Ward supported the Bellaire School for Girls. In one case, he sent a married 15 year old girl to the Bellaire facility. Her attorney insisted as a “married woman”, she was an adult. Judge Harvey disagreed and determined at 15 years old she was a juvenile. During this time, Texas suffragists were lobbying for the Texas law of consent to be raised to 18 years.

In March of 1915, Judge Harvey and Hortense Sparks Ward traveled to Washington for admission to the U. S. Supreme Court bar. They were the first married couple to achieve this honor and Hortense was the first Texas woman lawyer admitted.

Roadhouses outside Houston city limits sold beer. At one of these establishments, Eureka Pines, they sold beer to underaged girls and encouraged them to dance. The county attorney‘s investigation revealed numerous young girls were becoming delinquents and in the resulting hearing, Judge Harvey heard over 50 witnesses including a dozen girls assigned to the Bellaire Girls School. Judge Harvey revoked Eureka Pine’s liquor license and effectively put them out of business which shocked many area businessmen.

After his term ended, Judge Ward volunteered on the Houston/Harris County hospital board formed immediately after World War I to raise funds for the proposed public hospital named for Jefferson Davis in early 1924. Houston did not have a public hospital until this effort raised awareness of the desperate need to have a public health hospital in response to the Spanish Flu epidemic, returning veterans and the needs of the growing city.

William Ward’s early life was not easy. His father died in 1881 when young William was six. From that young age, he worked delivering newspapers and later as a railroad clerk. He graduated in 1902 from the University of Texas Law School and married Hortense Malsch in 1909. He decided not to run for a second term in 1916, but has the distinction of successfully running again twenty years later in 1932 for the same position. His second term is noted for a $4,000,000 bond to improve highways. Active in numerous fraternal and community organizations, he died at 59 in 1939. Harris County offices except for the tax collector’s office were closed so employees could attend Judge Ward’s funeral.

“For County Judge W.H. Ward,” The Houston Chronicle, 25 February 1912, p. 31, col.1.

”Judge Ward’s Funeral Rites Slated Friday,” The Houston Chronicle, 30 March 1939, p 1, col. 2.

“County Will Be Asked to Aid on City Hospital, Proponents Ask for Joint Bond Issues for Building, Proposed Bonds Total $2,325,000,” The Houston Post, 10 Feb 1922, p. 1, col. 4.

“City and County Hospital May be Constructed, Conference Held to Discuss Plans for Proper Care of Patients in the Advanced Stages of Tuberculosis” The Houston Chronicle, 20 October 1915, p. 13, col. 2.

“Six Young Girls from Delinquent School give Testimony that Decides Case in Mind of Judge Ward,” The Houston Chronicle, 9 September 1915, p1, col. 3. “Young Bride Must Remain in Girls’ School,” The Houston Chronicle, 26 November 1915, p. 4, col. 1.

“Offices Closed for Funeral of Judge Ward, Tax Collector’s Department Only One in Civil Courts Building Open as County Employees Attend Rites,” The Houston Chronicle, 31 March 1939, p. 48, col. 4.

“Harris County Sets Pace for South in Training Delinquent Juveniles, Boys of County, Many of Whom have not had a Fair Chance, are Taught Useful Trades and are Making Good; Recreation Plays Important Part in Transformation of Youthful Habits; County Judge Ward Explains Methods Employed,” The Houston Chronicle, 13 September 1914, p. 20, col. 1.

“Anniversary of School for Boys is Celebrated,” The Houston Chronicle, 29 May 1915, p. 4, col. 3.

“Harris County Fits Delinquent Youths for useful Citizenship, Success of Venture at South Houston Indicates Complete Solution of Problem,” The Houston Chronicle, 13 September 1914, p. 20, col. 1.

“Citizens File Protest to Tuberculosis Station Foot of Capitol Avenue,” The Houston Chronicle, 6 May 1913, p. 10, col. 3.

“Plan to Raise Fund to Fight White Plague,” The Houston Chronicle, 16 November 1913, p. 11, col. 5.

“T.B. Camp Will Feel A Revival,” The Houston Chronicle, 20 February 1916, p. 11, col. 6.

“Tag Day Officially Fixed for December 20th, Settlement and Anti-Tuberculosis League to Profit this Year,” The Houston Chronicle, 12 December 1915, p. 13, col. 1.

“Houston Woman has High Honor, First Texas Woman Admitted to Practice in U.S. Supreme Court,” The Houston Chronicle, 2 March 1915, p. 5, col. 1.

Edward Vincent Ley (1873-1952)

Real estate development has made many Houston fortunes from the time the Allen brothers began selling lots in 1836. 65 years later, Cora and Edward Vincent (E.V.) Ley moved from Iowa to find their fortune in Houston residential real estate development in sections built north of Buffalo Bayou. By 1908, Mr. Ley was developing a large 351 acre subdivision. He became prominent as a developer for opening up Woodland Terrace in 1915 and White Oak Addition in 1923. Cora was an active club woman and American Boy Scout supporter. Today, the Ley name is part of the Houston landscape with Ley Road, Rice University’s Ley Student Center, Rice University’s Ley Track and Field and Ley Family Y.M.C.A.

“Real Estate Deals, E.V. Ley Buys a Valuable Tract of Acreage Land, Conveyances Filed Record in the County Clerk’s Office Yesterday Aggregate $38,125,” Houston Daily Post, 2 September 1908, p. 13, col. 1.

“Houston Companies Charter, Two Concerns Incorporate to do Business in this City,” The Houston Post, 18 December 1908, p. 9, col. 1.

“Real Estate Deals,” The Houston Post, 20 April 1909, p. 13, col. 1.

“Mrs. Ley, One of City’s Developers, Dies in Hospital,” The Houston Chronicle, 17 January 1948, p. 1, col. 2.

“Ley—Mrs. Cora Durer,” The Houston Chronicle, 18 January 1948, p. 44, col. 7.

“The Kensington Club,” The Houston Chronicle, 11 November 1919, p. 7, col. 2.

Find a Grave, Edward Vincent Ley Memorial Page. https://www.google.com/search?source=hp&ei=bodBX4zLJMrUsAWj2J34BA&q=%22find+a+Grave%22+&oq=%22find+a+Grave%22+&gs_lcp=CgZwc3ktYWIQDDICCAAyAggAMgIIADICCAAyAggAMgIIADICCAAyAggAMgIIADICCAA6CwguELEDEMcBEKMCOggILhCxAxCDAToICAAQsQMQgwE6DgguELEDEIMBEMcBEKMCOgUIABCxAzoRCC4QsQMQgwEQxwEQowIQkwI6CAguEMcBEKMCOgUILhCxAzoICC4QxwEQrwFQxQlY4S9gmDtoAHAAeACAAUqIAf4GkgECMTWYAQCgAQGqAQdnd3Mtd2l6&sclient=psy-ab&ved=0ahUKEwiMup2m2q_rAhVKKqwKHSNsB08Q4dUDCAg# “Park Place Developer Dies at 78,” The Houston Chronicle, 18 January 1952, p. 18, col. 3.

“Boy Scout News,“ The Houston Chronicle, 20 April 1924, p.7, col. 5.

“How Judge J.D. Harvey Once Brought Waller County Back Into Democratic Fold is Told By Boyhood Acquaintances,” The Houston Chronicle, 7 July 1924, p. 10, col. 5.↩︎

“Women’s Clubs Solicit Aid for Child Support Bill,” The Houston Post, 18 December 1920, p. 10, col. 5.↩︎

The Houston Chronicle, Wed. July 16, 1924, See also “Child Support Bill Fight Just Beginning—Harvey,” The Houston Post, 13 February 1921, p. 31, col. 8.↩︎

“Unusual Angle to Divorce Record of Judge J.D. Harvey is Uncovered; is Victim of Laws He Would Change,” The Houston Chronicle, 16 July 1924, p. 3, col. 3.↩︎

“Judge Harvey Given Post On Appeals Body, Former Houston Jurist is Named for Six-Year Term on Commission of Appeals,” The Houston Chronicle, 26 June 1925, p. 1, col. 3.↩︎

“How Judge J.D. Harvey Once Brought Waller County Back Into Democratic Fold is Told by Boyhood Acquaintances,” The Houston Chronicle, 7 July 1924 p.10, col.2.↩︎